MEMBERS SHOULD LOG IN FIRST TO ACCESS FULL ARTICLES

|

Immigrants in Aviation - Rotorcraft: Rotor-Revolutionaries from Abroad Too seldom recognized in American aviation historiography is the enormously formative foreign But, also, many major "American" aerospace developments have actually been the product of foreign-born immigrants, or their children. From Chicago-Frenchman Octave Chanute’s trend-setting gliders (largely imitated by the Wrights), to German rocket scientist Werner Von Braun’s virtual invention of U.S. spaceflight, America has depended on immigrantingenuity for much of its aerospace progress. Nowhere in American aviation are the impacts of immigrants and their offspring more obvious than in the world of rotary-winged aircraft. Various nations have lost much of their vertical-flight talent to the U.S. - the former Soviet Union in particular. Many Russians and neighboring ethnics fled the October 1917 revolution, as it turned the brutal Czar’s Russian Empire into a civil-war hell-hole, degenerating into the pseudo-communist Soviet Union police state. Among those fleeing were many of that empire’s educated and scientific elite, including three of the greatest helicopter pioneers in history.[1] Other immigrants beget fellow founders of "American" vertical flight. DeBOTHEZAT Among the immigrants was the "Mad Russian" aeronautical engineer Prof. George deBothezat. Arriving in the U.S., he crafted the U.S. Army’s first helicopter – a massive four-rotor contraption that, in the early 1920s, hovered, with very limited control, in ground effect. By April 1923, it lifted the pilot and three passengers 10 feet off the ground in a hover, then 30 feet – not yet useful, but a vertical lift unmatched for the next two decades. The U.S. Army, alas, saw no value in continuing the $200,000 project.[2] BERLINER German-Jewish immigrant Emile Berliner, a prolific inventor, was another rotorcraft pioneer. Upon inventing the common, loose-carbon telephone transmitter (microphone), he was hired into the fledgling American Bell Telephone company, engineering there for seven years, helping fellow immigrant Alexander Graham Bell turn the telephone into a practical appliance. Emile then invented the gramophone – forerunner of the phonograph - and the flat recording disk (now known as a “phonograph record”), eclipsing Thomas Edison’s awkward recording cylinders. This facilitated mass production of recordings, creating the recording industry and the corporate beginnings of pioneering audio/radio/TV/avionics colossus RCA. Berliner invented acoustic tiles that transformed concert halls, and even parquet flooring. And a few early helicopters.[3] With his son Henry, Emile designed and built rudimentary experimental helicopters from 1907-1926. His earliest two helicopters were powered by the world’s first airborne rotary engines, adapted by Emile. Their early helos flew, briefly - including one, flying a minute and a half, up to 100 yards, in 1924. Their 1924 Helicoplane flew sideways 400 yards, up to 40 mph, and 30 feet vertically, above ground effect, under control[4] Their rotor-aircraft - including a triplane with twin main rotors over the wings and a horizontal tail rotor - weren’t particularlycontrollable. But they’d showed that helicopters could truly fly.[5] In 1920, they established Berliner Aircraft Co. (becoming Berliner-Joyce in 1929).[6] Then, in the early 1930s, son Henry started Engineering Research Co. ("ERCO"), soon famous fortheir pioneering lightplane: "ERCOupe"[7] – later "Ercoupe", then “Aircoupe.” Designed by Fred Weick – with tricyclelanding gear, aluminum/semi-monocoque fuselage, and cantilever-wings – it was the first "modern" general aviation airplane. Sold by the thousands, it was one of the most popular and influential light planes of the 20th Century.[8] SIKORSKY Russian Igor Sikorsky, was born in Kiev (capital of today’s Ukraine),[9] with aviation training in Paris, and Kiev’s Polytechnic Institute.[10] By 1909, he had developed a crude, under-powered helicopter[11] using counter-rotating rotors - though it was uncontrollable and couldn’t lift more than itself.[12] He switched . . . |

|

|

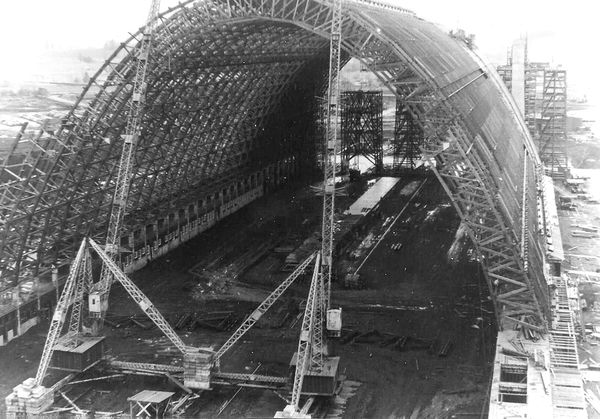

Coastal Sentinels; The Rise and Fall of the Blimp Hangar In the film (and novel) Twelve O’Clock High, Harvey Stovall, the 918th Bomb Group’s adjutant, pays a sentimental visit - several years after the end of the War - to Archbury, the group’s deserted air base. As he walks among overgrown runways, the decaying barracks and abandoned control tower, he remembers. He hears the roar of ghostly Flying Fortresses; he sees the scurrying of ground and medical personnel and, most poignantly, he hears the singing of the young men. The ruined airfield remains as a monument to those who lived and served their country in a time of need. A visitor to the mighty "lighter than air" (LTA) hangars at several airfields on America’s coasts gets that same feeling today. Once there were 17 of them; now only seven survive. Colossal hangars, “temporary” structures built during WWII to house America’s LTA "blimp" squadrons, are a marvel of architectural ingenuity. Once housing eight or more 250-foot-long, 60-foot-wide, K-class Navy airships, these monstrous hangars are almost 1,100 feet long, 300 feet wide and 15 stories high. They remain as a memorial to a time when airships played a critical role in defending America’s coastlines and ship convoys. In fact, once the blimps became operational in defending allied convoys, not one ship protected by a "poopy bag" was ever lost to an enemy submarine attack. Of course, hangars for blimps were necessary long before WWII. The Germans had led the way in design of LTA ships before WWI with their development of "duralumin." This material was instrumental in the creation of "rigid" airships – a lightweight, strong frame with a fabric covering, or "envelope." Hydrogen-filled bladders inside the frame provided the lift. The Graf Zeppelin and mighty Hindenburg were so impressive that other countries rushed to keep up with the German designs. Between the two World Wars, the United States had a fledgling airship program that was promoted by the Navy and approved by Congress. During WWI, Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. built America’s first LTA base at Wingfoot Lake, near Akron, Ohio. This facility was intended to house and service huge airships such as the Shenandoah; it even had a hydrogen processing plant nearby. In 1921, the first fully operational Naval Air Station was established at Lakehurst, New Jersey. Both locations eventually became primary construction and testing sites for America’s LTA program, both civilian and military, for decades to come. |

|

|

The Ho Chi Minh Trail The Ho Chi Minh Trail was a network of roads running through Laos that comprised North Vietnam’s logistic communications and supply route into South Vietnam. Originally a centuries-old trail of footpaths, the North Vietnamese began improvements in 1959 to supply the Viet Cong insurgency against South Vietnam. By 1961, trucks began supplanting bicycles and ox carts transporting supplies along dirt roads 18 feet wide, capable of two-way traffic, concealed under the triple canopy and artificial camouflage. By 1965, 195 tons of the North Vietnamese (NVN) daily requirement of 234 tons of supplies was flowing through Laos, as well as thousands of troops. Road improvements continued, and by late-1967, 2,959 km (1838.6 miles) of vehicle-capable roads had been completed. In 1968, a petroleum pipeline was discovered that crossed into Laos through Mu Gia Pass. Operation Commando Hunt also began in 1968, and its effectiveness forced the NVN transportation units to travel only from dusk to dawn. During this period, the U.S. threat increased due to the heavy concentrations of anti-aircraft artillery (AAA), with 23mm, 37mm, and 57mm guns to include from 1969, 85mm and even 100mm weapons. Estimates indicate that by the end of Commando Hunt, the trail was guarded by 1,500 guns. How I Got There In the summer of 1968, following graduation from the University of Wisconsin under an Air Force-sponsored master’’s degree program in international relations, I was rewarded with an assignment to Southeast Asia in the F-4D. At that time, I was a captain and a navigator with just under 5,000 hours in the C-124 Globemaster and C-141 Starlifter. Following sea survival training at Homestead AFB, Fla., and radar lead-in training at Davis Monthan AFB, Ariz., I arrived at George AFB for training in the F-4D Phantom II to become a weapons systems officer (WSO), aka "guy in back" (GiB). I was fortunate to be crewed with Lt. Col. Robert "Bob" Vanden-Heuvel, a former F-4 test pilot. Bob was short in stature, but he was an excellent pilot. I took much ribbing from him since he often told me he’d rather have a gas tank where the back seat is rather than someone sitting there. At the same time, however, he taught me much about how to fly the F-4, breaking the rule that said backseat non-pilots needed to learn how to recover from unusual attitudes. Sounds good except the "unusual attitudes" could not exceed 10 degrees in either axis - up, down, right, or left. Thanks to Bob, I became an excellent wingman in all attitudes and his lessons helped save my life and that of my pilot one stormy night over Laos. The training at George AFB included 131 hours in the F-4D learning all the things we were supposed to learn. I also learned that there is danger and death even in a training situation. During the night portion of our training, just before graduation, the crew that vied with Bob and me for top gun, and just about 15-20 minutes ahead of us, "pressed" on the target, trying to get a good bomb score. Unfortunately, they pressed too low and crashed, killing both the pilot and backseater. Bob’s repeated remarks would have scared me if I had known then what my next assignment would be: "Night and fighter pilots don’t mix," were his words, or words to that effect. Two weeks before departing George AFB, I learned that I was being assigned to Royal Thai Air Force Base (RTAFB)

. . . |

|

|

That morning in January 1971 was a terrible day for flying, thunderstorms everywhere; three hours of misery flying through turbulence and rain. I was supposed to be patrolling the southern part of the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos looking for signs of North Vietnam trucks hidden after their nightly run down the Trail. But that day, I was wasting my time. I was a young Air Force 1st Lieutenant, recently out of pilot training, now a full- fledged Forward Air Controller (FAC) flying an OV-10 Bronco with the 23rd TASS out of Nakhon Phanom (NKP)Thailand. In this filthy weather, I had been doing my best to keep the multiple dirt roads of the Trail in sight while staying at our usual visual search altitude of 5,000 feet above the ground. Any lower would-be big trouble, the anti-aircraft guns protecting the Trail would make quick work of a single OV-10. Unfortunately, on this nasty day, the thunderstorms had bases of about 3500 feet and topped out well above any altitude my OV-10 could reach. So, with no good options, I flew directly into the storm cells, with turbulence so bad that my helmet was continually banging into the canopy, and my binoculars and map case became dangerous missiles flying around the cockpit. "OK, enough is enough," I said. I gave up and took up an approximate heading toward home at NKP a couple of hundred miles away. The OV-10 had multiple radios, but no real navigation systems to help lead me home, no Inertial Nav, no GPS, nothing but a compass and one old Tacan receiver. Picking up an approximated heading while plowing through the storms was the best I could do. Again, the turbulence and heavy rain in the thunderstorms was terrible, so I reluctantly descended hoping I could get out of the clouds and turbulence and miss the guns. At about 3,000 feet above ground I broke out, and could begin to see the terrain through the mist and rain. As the view became clearer, a river appeared, then shockingly, I realized that the river was not just one but several that joined to form the distinct shape of the letter "H." The land surrounding the "H" looked like the surface of the moon, bomb craters stretched in every direction. Only one place on the Trail had river junctions shaped like an "H,": Tchepone, the most feared area of the Ho Chi Minh trail for American pilots. I had blundered right over it, well within the range of North Vietnamese (NVA) big guns. The village of Tchepone was on Route 9, the main east-west section of the Trail. The other active roads of the southern section of the Trail joined Route 9 near Tchepone. The NVA had owned the area for years and because of its strategic location, had honeycombed it with storage areas, protected by 23mm, 37mm and 57mm radar guided Russian guns. Tchepone was the site of many, many, American aircraft losses, blown out of the sky by the nasty big guns followed by rescue efforts that often resulted in the loss of even more aircraft. Through the rain I could make out remnants of the old French mining village that had stood there before the war, bombed-out hulks of buildings among the ugly landscape of bomb craters.

Suddenly the ground lit up with flashes, then streams of yellow tracers flew at me like water from a hose. Big colored fire balls floated up, exploding around me in flak filled black . . . |

|

|

The Story of the Self-Sealing Fuel Tank About a year ago [1945] there appeared in a magazine a short article on the self-sealing of airplane fuel tanks that stated that such tanks had been developed in WWI and that their use in WWII was nothing new. That, undoubtedly, is entirely true and nobody ever intended to belittle the efforts, or the results of those efforts, of those pioneers who tried to change the old "flying coffins" into something a little more habitable for the aviators who were unfortunate enough to catch an enemy tracer or incendiary bullet in the gasoline tank. The self-sealing or, as it is commonly and erroneously called, the bullet-sealing gasoline tank, as we know it today is something as different from what the WWI model must have been as night is from day. Of course, the objective was the same in each case but that is about all that can be said for any similarity, or we would have heard more about the early models and, most certainly, we should have had more of a background at least to get a good start on the tanks of WWII. As it was, we had little or nothing. It is the purpose of this article to tell something of the surprises, troubles, and successes that were encountered in the development of the self-sealing gasoline tank of today; a development that is now as much a part of every American combat airplane as its engines or wings but has become so commonplace that it is taken for granted. As far as the United States Navy is concerned the real development of the self-sealing gasoline tank started with the first gunfire tests conducted by personnel of the Naval Air Detail of the Naval Proving Ground at Dahlgren, Va., in the middle of 1940. Late in the year 1939 several tanks had been tested by Lt. Comdr. William S. Parsons, U.S. Navy, who at the time was Experimental Officer at the Naval Proving Ground. The Bureau of Aeronautics was of course integrating all of the design, manufacturing, and test work for the tank, since that was and still is the cognizant bureau, but as it had no adequate gunfire test facilities of its own at that time, that phase of the work was done by the Bureau of Ordnance for the Bureau of Aeronautics. Aviation personnel at Dahlgren conducted the gunfire tests. The war in Europe had already indicated that both the English and the Germans had some type of self-sealing tanks and armor in their combat airplanes and farsighted personnel in the Bureau of Aeronautics immediately saw the hand writing on the wall and initiated the development for our own service. They also reasoned correctly that since we were using .50-caliber machine guns, any potential enemy might, and probably would, do the same and they specified, therefore, practically from the start of the tests, that all of our self-sealing tanks be designed to withstand .50-caliber bullet impacts. Except for a few shots fired out of pure curiosity from a .30-caliber machine gun in order to compare it with the larger gun, all tanks were tested with the .50-caliber gun. The wisdom of the Bureau of Aeronautics personnel in specifying this gun will be brought out later. There immediately comes to mind that the 20-mm gun firing an explosive shell was already in use. So what were we going to do about that? The answer to that is that it was expected that an unfortunate 20-mm hit was too much to protect against, and that in such a case the tank would leak and the airplane might even be set on fire. That this was not always so will also be seen later. Just how much research, calculating, burning of midnight oil, and garden variety of guessing on the part of the people in the U.S. rubber industry went into the construction of the first tanks no one will ever know. At that time none of the companies had their own gunfire test ranges, which they later set up to make preliminary tests and throw out ideas that obviously were no good, so that the first gunfire tests the self-sealing tank designers saw at Dahlgren were surprising and discouraging, to say the least. It was no less discouraging and surprising to the personnel at Dahlgren because it looked like a losing battle from the beginning. To one who does not know about the devastating power of our .50-caliber machine gun (it is considered a cannon by European standards) the normal reaction is to think that a hole made in rubber by a .50-caliber bullet should not be difficult to . . . |

|

|

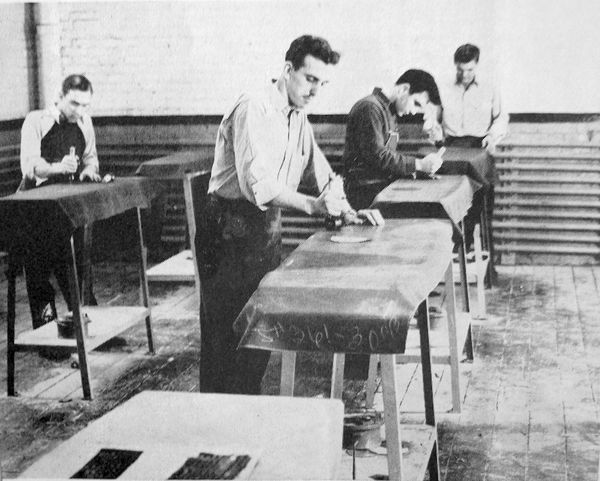

Countering the Zero: A Small Firm’s Contribution It didn’t take long after the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor for American pilots to fear engaging the Japanese "Zero" fighter plane in combat. Time and again, the agile Mitsubishi A6M would out-turn its rival in dogfights, allowing skilled Japanese pilots to gain the aerial advantage. Lightweight construction, positioning its engine and fuel tanks close to the cockpit and employing a lightened empennage produced a reduced moment of inertia. This "second moment of mass" describes a vehicle’s resistance to rotational motion. The low weight of the A6M also enabled it to out climb rivals. The design of U.S. fighter aircraft stressed heavy firepower, durability, and pilot protection, including both armor and fuel security. In addition, the airframes of Navy aircraft such as the Grumman F4F-3 and F4F-4 were more heavily constructed than land-based fighters like the Curtiss P-40. This helped them overcome the rigors of landing on aircraft carriers. Together, these features resulted in more weight, increased moments of inertia, and lessened climbing capability. By mid-1942, however, new tactics were devised that countered some of the Zero’s inherent advantages. Tactics included the "Thach Weave," an aerial combat maneuver developed by Navy pilot John S. Thach. And in 1943, superior carrier fighters including the Grumman F6F Hellcat and the Vought F4U Corsair arrived to support the Pacific fleet. When taking fire, Mitsubishi A6M Zeros often burst into flame or exploded, because they lacked the self-sealing fuel tanks that protected American flyers. In contrast, Japanese pilots complained that multiple salvos fired into U.S. fighters often failed to hinder their flight. The self-sealing fuel tanks (also called fuel cells) of U.S. aircraft were constructed of layers of reinforced fabric and rubber. Entrance holes made by bullets were quickly sealed by the action of the gasoline on untreated rubber. The rubber swelled and closed the hole, preventing massive leakage and possible ignition and/or explosion. However, laboratory experiments reported in the 1946 Naval Institute Proceedings showed that a bullet’s high-speed impact often burst slab-sided tanks. As Edward Eckelmeyer, Jr. wrote in Vol. 72/2/516 [see previous article], this was only avoided by building the tank as a unitary construction, carrying alternate layers of materials around rounded corners to adjacent sides to distribute the stresses of impact. This measure complicated the cell’s construction in two ways: First, the entire cell had to be constructed at one time rather than assembled from separate parts. Second, it had to be built over a form. The form duplicated the inside configuration and dimensions of the completed cell. It provided the base upon which a worker would successively accumulate layers of reinforced fabric and rubber. This construction technique required the form to be removed before the fuel cell could be installed—a difficulty that was not easily overcome. My uncle, Serge A. Rivard (1905-1987), proposed that the form for a fuel cell be made of corrugated cardboard. Piping live steam into the fuel cell’s interior would collapse the cardboard. Within a short time, the hot steam would reduce the cardboard to its original nature as wood-pulp and water. Subsequent flushing via its hose connections removed the pulp-water mix from the cell. After cleaning and drying, the empty fuel cell was now ready to be installed in a warplane on its assembly line. The United States Rubber Company in the small town of Mishawaka, Ind., accepted the concept and Rivard Products Company was formed to produce the needed cardboard forms. Within months, an existing warehouse on the bank of the St. Joseph River was leased and production of forms begun. My father, Earl J. Rivard (1907-1996), Serge’s brother, became the . . . |

|

|

The 737 and the Thrust Reverser, or, Just one more Day! Have you ever wondered why some things can’t last just one more day? Just one more damned day! OK, here’s a couple of examples. I started to notice while flying my airplane that the engine starts were getting a little "anemic." I checked the battery - it tested good, but I figured it was getting close to giving up the ghost. So I bought a new one. It arrived, and I took it to the hangar one Saturday morning, placing it on the bench. I needed to make a quick flight over to Paine Field to give a tour of our B-52 to a few friends from Texas (Jim Gabriel - the original pilot of that very B-52 in Viet Nam). When I got back, I’d be wisely pre-emptive and change the battery. So I jumped in and hit the starter - and - nothing. The battery was dead. So, I had to change the battery, which took about an hour - before my flight, instead of after. Now why couldn’t it have lasted one more flight??? Just one more flight? See what I I mean? Another example - also on my airplane. The RV-12 fleet was having bad problems with the Voltage Regulator - a unit made by Ducati, in Italy. Reading other people’s problems, I carefully monitored all my engine parameters on my computer after every flight, and although all was good, decided to beat Fate and install a new one from a different vendor (actually, a John Deere lawn tractor VR - something you can do on an Experimental airplane!) I bought the new JD regulator and ordered wire and connectors from SteinAir in Minnesota. During my Annual Inspection, I installed the new Regulator in a new location - it was a Thursday. My wiring was due on Monday. In the interim, I flew down to Sonoma California to fly my friend Chris’s Curtiss P-40. When I got back, on Monday or Tuesday, I was going to hook up the new VR. But wait! On the return flight - Saturday - my Voltage Regulator gave up the ghost around Medford, Oregon. I ducked into Cottage Grove, where fortunately, a good Samaritan named Ron English fabbed a temporary (5 years later - still installed) wire bundle for me to connect to my already installed new VR, to get me home. OK, Sky Gods, all that VR had to do was last one more flight - one stinkin’ more flight - and all would be good. But No - they couldn’t do it. They always seem to have to prove that THEY are in charge! So, here’s a story about a Boeing 737 where the same Sky Gods decided to play dirty tricks and deny the airplane just One More Day. When the Boeing 737 was designed, Boeing decided to utilize maximum commonality with the Boeing 727. It had the same body, same cockpit, same engines, same system architecture - A & B hydraulic systems, Standby system, same pressurization system. On and on. One thing it had were the same thrust reversers. The 727 thrust reversers, IMHO, weren’t very good. First, they were pneumatically operated. In my experience, pneumatically operated systems were poor performers and unreliable. The 707 and 747 fan reversers operated that way; so did the 747 leading edge flap drives. Hydraulically driven units were 1000 % better. But then, I don’t design ‘em. I ‘jes fix ’em. The 727 thrust reversers had six parts: two clamshell doors inside the tailpipe that closed and blocked the exhaust gases; two sets of cascade vanes that redirected the exhaust gas flow; and two sets of deflector doors that aimed the redirected exhaust gases forward. The deflector doors were the problem. They were semi-hemispherical doors that were attached with a four bar linkage. Those bars would often break, and the door would depart the airplane. LaGuardia Airport police would drive me out to the runway with some frequency to pick up the departed deflector doors. Their reliability was so poor, that airlines began leaving them off altogether. The doors were on the MEL (Minimum Equipment List), meaning the airplane could be flown for limited periods without them, so the airlines petitioned to make that permanent - and approval was granted. In the latter part of the 727s service life, very few airplanes retained the deflector doors. Now, on the 737, the exact same reverser was fitted to the airplane’s engines. The deflector doors opened horizontally, like the center engine on the 727. But the problem on the 737 was that, with the flaps extended to 30 or 40 degrees for landing, the reverse thrust exhaust gases became trapped between . . . |

|

|

The Irish Swoop....the Bellanca 28-70 The MacRobertson Air Race Civic leaders in Melbourne, Australia decided to celebrate the centenary of the city with an international air race from England to Melbourne in October 1934. The wealthy Australian candy manufacturer Macpherson Robertson put up the prize money of $60,000 so it became the MacRobertson Race. The British Royal Aero Club fully supported the race, and arranged a string of 22 refuelling points across the British Empire with the Shell and Stanavo oil companies including five compulsory stops at Baghdad, Allahabad, Singapore, Darwin and Charleville. The Irish Aviator, Col. James Fitzmaurice, who had successfully flown the Atlantic E-W in a Junkers monoplane Bremen in April 1928 with the Germans Koehl and von Huenefeld , was sponsored in the race by the Irish Hospitals sweepstakes. Fitzmaurice, injured during his three years in the British Army in WWI, had transferred to the Royal Flying Corps for flying training in 1918 but the war ended just as he got his license. Following Irish independence in 1919 he had built up the infant Irish Air Corps and was its commandant by 1934. 5 Months from Drawing Board to Flight Fritzmaurice who had teamed up with Eric ‘Jock’ Bonar during the 1933 British Hospitals Air Pageant tour, could not find a suitable British plane so they went to America to commission a racer with the range and speed for the 11,300 mile race and on May 14 accepted Giuseppe Bellanca’s proposal to build one in five months for $30,000. (The De Havilland company had nine months to develop their Comet racers) Bellanca had working for him in Delaware the young designer Al Mooney (he had designed the very efficient 15-seater Bellanca Airbus design, whose single engine restricted U.S. commercial use). For the Bellanca 28-70 racer Mooney moved away from the high wing slab-sided fixed landing gear formula that had been so successful in Atlantic crossing attempts. He proposed a cable braced thin-section low-wing monoplane with a circular fuselage and retractable landing gear to raise the cruising speed into the 250-mph bracket. Mooney used a ‘conventional’ welded steel tube fuselage with thin wood-strip stringers covered with doped fabric, with an enclosed acrylic cockpit blending into the tail fin (so restricting the pilots ground visibility). The wing had wooden ribs formed by Bellanca’s skilled Italian immigrant carpenters and was again fabric clad and doped. Perhaps the most unusual (and worrying?) feature was the pair of vertical metal bracing posts directly below the fuselage (and its large long-range fuel tank!), these supported the lower bracing cables for the wing. Fitzmaurice returned to the U.S. in early August to find the 28-70 structure nearly complete but not yet fabric covered. The first engine run-up was achieved in the eleventh week but the Wasp Junior radial (a lucky surplus find from a U.S. Navy program) hit cooling problems requiring rework of the cowling. On September 1, Bellanca’s test pilot Leon Allen made the first flight of the Swoop, followed by intensive work through September revising the sloppy aileron controls and inadequate cowling/cooling. Fitzmaurice and Bonar took turns assisting from the copilot’s seat. Finally Allen flew the Swoop to Floyd Bennett field, N.Y., where the load tests were carried out on September 28. The aircraft was then taxied via the seaplane ramp onto a harbour lighter barge for crane transfer as deck cargo on the ocean liner Bremen bound for Southampton, U.K. Rough weather off Southampton prevented the planned crane transfer of the Swoop to a barge so it had to stay on board until arrival at Bremerhaven in Germany where it was . . . |

|

|

Lockheed’s RT-33As Supplied to U.S. Allied Nations in the 1950s and 1960s This article is a comprehensive review of all the Lockheed RT-33As supplied to U.S.’s allied nations in the 1950s and 1960s. Since the RT-33As were not originally intended for USAF, there is very little documentation in most aviation books published in the U.S. Most have just one or two lines mentioning the existence of this variant. There are books on the RT-33A published in nations that operated the RT-33As. Some are very precise, but some are not in documenting the identities of the RT-33As supplied. A good amount of time has been spent researching and tracing the identities of individual RT-33As supplied to different nations. The following represents the most accurate data that has been compiled to date. There are inconsistencies in some of the USAF documents referenced and a few judgment calls have been made after reviewing other relevant sources. There is always room for improvement. Readers’ feedback and corrections are kindly solicited. There is a mixed use of the terms “MAP” and “MDAP” in this article. According to the explanation in Ref. 5, they are essentially the same:

"The Mutual Defense Assistance Program (MDAP) was created by the Mutual Defense Assistance (MDA) Act of October 6, 1949 – 6 months after the North Atlantic Treaty was signed. The MDAP became the Military Assistance Program (MAP) five years later. The new program reflected changes in the basic legislation of the MDA Act, effective August 26, 1954, (The MDAP designation lingered a while longer.) Mutual Security Act of 1954." The term, MAP, was not officially used in the USAF Digest until its Fiscal Year 1957 edition. The Lockheed RT-33A Lockheed’s RT-33A is a version of the T-33A trainer, modified into a single seat photo-reconnaissance aircraft. The nose section was significantly modified to accommodate various cameras very similar to the latest version of the camera arrangement in the RF-80C. Due to the number of cameras carried and the addition of a wire recorder, the loop antenna placed in the nose section was pushed further forward forcing Lockheed to modify the nose contour of the RT-33A. This made it more square-looking. The second seat of the aircraft was removed and modified to carry more fuel and the AN/ARN-6 radio compass and the AN/ARC-27 transceiver. These two pieces of electronic equipment were located in the nose section of the T-33A. The canopy of RT-33A remained the same as that of the T-33A. The dimensions of RT-33A and T-33A are identical except the length of RT-33A is 2.4 inches shorter (RT-33A length: 37.5 feet; T-33A length: 37.7 feet). The revised nose contour and the camera windows make the RT-33A readily distinguishable from T-33A. The cameras installed in the nose section are divided into three camera bays: forward, middle, and aft with a total of four cameras. The forward bay contains one K-22A camera with a 12-inch lens positioned in the forward oblique position. The middle bay contains two K-17C cameras each with a 6-inch lens; one aimed towards the left oblique position and the second aimed towards the right oblique position. These are the side-view cameras. The aft bay contains one K-38 camera with a 24-inch lens in the vertical position. The RT-33A also carried a wire recorder (AN/ANH-2) to enable the pilot to make a record of the flight over the target, to elaborate on particular features of . . . |

|

|

PBY Operations in the Solomons; A WWII Interview During WWII, the U.S. Navy interviewed hundreds of personnel about their service experiences, mostly combat related. Transcripts of the interviews were printed and forwarded to the organizations most likely to benefit from the interviewee’s comments and answers to questions. Digital scans of these transcripts are available online at the National Archives website, https://www.archives.gov/research. A recent search for details of a particular Navy patrol squadron turned up an interview that, while not yielding precisely the information sought, proved to be a very enlightening discussion of patrol squadron (VP) activity during Guadalcanal campaign. The interviewee was then Lt. Cmdr. J. O. Cobb, fresh from a tour of duty in the South Pacific. James Outterson Cobb (1910-2008) graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1933. In 1936 he was detached for flight training, winning his wings as a naval aviator the next year. Cobb served with VB-3 aboard the USS Saratoga before moving to a cruiser scouting squadron then to patrol squadron duty at Pearl Harbor, where he flew with VP-11, then as commanding officer of VP-91. Both squadrons operated the Consolidated the PBY-5 Catalina flying boat. Post war, Cobb went on to serve in billets of increasing responsibility, including executive officer of an escort carrier and command of the USS Yorktown (CVA-10). Promoted to flag rank, he retired as a rear admiral in 1971. In this wide-ranging 1943 interview, Lt. Commander Cobb addressed a number of topics, including combat operations but also touching on such seemingly mundane matters as tropical clothing and taking Vitamin A to improve night vision. His comments and criticisms, along with the Bureau of Aeronautics responses, when made, provide insight into aspects of the Pacific War rarely examined in commercially published personal memoirs The text presented here is a verbatim transcript of the scanned typescript interview downloaded from the National Archives. The interview was conducted in the middle of a brutal war; cultural sensitivity was not an issue. Words inserted for clarification are enclosed in brackets. Editorial comments, also enclosed in brackets, are in italics. Information which is relevant but not essential to understanding the transcribed narrative is appended as footnotes.

Interview of Lieutenant Commander J.O. Cobb, USN Operations of Patrol Planes in the Solomons Campaign After the Battle of Midway we began moving planes down into the vicinity of New Caledonia, with the idea of either putting up a fight for New Caledonia or, as it developed, commencing an offensive. The patrol planes moved into Espiritu Santo just a few weeks before our seizure of the Solomons. Espiritu has turned out to be the most important base in that area, and in my opinion probably one of the places with the greatest future possibilities for a naval base. [Espiritu Santo, in the modern nation of Vanuatu, lies roughly 600 miles southeast of Guadalcanal.] Another group, VP-23, on the [August] 7th moved into Malaita [the large island across Indispensable Strait, east of Guadalcanal.] This miscellaneous group of which I had charge, VP-11 and VP-14, with the McFarland as tender, covered the northern flank of the Solomons. Fortunately, the whole operation was a complete surprise to the Japs, we ran into almost no . . . |

|

|

This issue of the Forum focuses on uncataloged images from the AAHS archives donated by Charles "Chuck" Stewart focusing on aireal tanker operations from the 1990s to mid-2010s. These images, and thousands more, are targeted for processing in AAHSPlaneSpotter where volunteers assist in cataloging them. Interested in helping? Go to www.AAHSPlaneSpotter.com and check the system out. The FORUM is presented as an opportunity for each member to participate in the Journal by submitting interesting or unusual photographs. Most of the images come from contributions to the AAHS archives. Unfortunately, with older images the contributor information has been lost. Where known, we acknowledge them. Negatives, slides, black-and-white, or color photos with good contrast may be used if they have smooth surfaces. Digital submissions are also acceptable, but please provide high resolution images (>3,000 pixels wide). Please include as much information as possible about the image such as: date, place, msn (manufacturer’s serial number), names, etc., plus proper photo credit (it may be from your collection but taken by another photographer). Send submissions to the Editorial Committee marked "Forum of Flight," P.O. Box 483, Riverside, CA 92502-0483. Mark any material to be returned: "Return to (your name and complete address)." Or you may wish to have your

material added to the AAHS photo archives. |

|

American Aviation Historical Society

American Aviation Historical Society