|

Excerpts

from

|

||||||

|

America’s Local Service Airlines, Part IV: Ozark, Pacific & PiedmontÂ

OZARK AIR LINES Like several other local service carriers, Ozark got its first experience operating an intrastate service. However, it was five years from the time that the intrastate operation in Missouri was shut down until Ozark Air Lines once again became airborne.

Ozark was the brainchild of Laddie Hamilton, who had transportation in his blood. Born June 28, 1910, Laddie’s given name was Homer Dale Hamilton. His father worked for the St. Louis – San Francisco Railway (The Frisco). After operating his own automobile garage in Springfield, Mo., Laddie went to work for Floyd W. Jones, first as a bus driver, then, in 1936, as manager of the southern portion of Jones’s Mo-Ark Coaches (later Mo-Ark Trailways). Floyd Jones and Laddie Hamilton developed a business relationship that would serve them both well for many years to come.

With Jones’s help, in 1937 Hamilton purchased the bankrupt Dixie Coaches, a bus line operating in Alabama and Mississippi. He resuscitated the company, turning it into a

financially-healthy enterprise, then sold it for a profit to Southeastern Greyhound Lines in 1942.

Laddie Hamilton had earned his pilot’s license in 1928, so it was no surprise that his next move would be into the field of aviation. He was training pilots during the war working for Oliver Parks’s Alabama Institute of Aeronautics part-time while acting as regional manager for Southeastern Greyhound Lines in Tuscaloosa.

On a spring day in 1943, he met with his friend, Floyd Jones, and two other gentlemen, Barak T. Mattingly and Arthur Heyne, both attorneys, at Mattingly’s office in the Title Guarantee Building on Chestnut Street in Downtown St. Louis. The purpose of their meeting was to discuss forming an intrastate airline that would operate between Springfield, St. Louis, Kansas City and Columbia, Missouri.

Articles of Incorporation were filed with the Missouri Secretary of State on August 26, 1943, and a charter was granted on September 1. Ozark Airlines was officially in business (note that “Airlines” was one word in the original incarnation of Ozark). Ozark was formed with the intent of starting one of the new “feeder” airlines that the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) was contemplating. The four founders felt that the CAB would look more favorably upon a company that had intrastate operating experience when it came time to issue the Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity, required for interstate operation.

Ozark started getting its experience by offering charter services out of Springfield. Then, with three Beech Modelt . . .

|

|

|

Introduction Jack Randolph Cram was hired in 1935 by the city of Olympia, Wash., to be the first manager of the 24-yearold Olympia Airport. He was already the first Washington State pilot, working for the Highway Department. Aviation activities on the field began with the first air show in 1911 on the Bush Prairie Airfield Site, south of neighboring Tumwater, Washington. In 1928, the Aviation Committee of the Olympia Chamber of Commerce spent $35,000 to buy 196 acres. Over time, the airport grew to three turf runways, typical of airports of the day. More land was purchased in 1929. With a manager in place, major improvements were made. In time, Cram went on to work with the federal Civil Aeronautics Administration before going on active duty in 1941. He became a heroic USMC aviator in the Pacific Theater. Later, he commanded Marine units in the Pacific and during the Korean War, eventually retiring as a brigadier general. Subsequent to retirement, Cram served as president of an aviation industry association. Background Jack Cram was born in Berkeley, Calif., on February 25, 1906. He had three older sisters and a younger brother. The family later moved to Washington state, where Cram attended the University of Washington. There, he made a name for himself as a football player and track star. He graduated from the university in 1929. In 1930, Cram enlisted in the USMC Reserve, which sent him to flight training at Naval Air Station (NAS) Sand Point, in Seattle, Wash., and NAS Pensacola, Florida. During the next three years, he became friends with fellow pilot Gwin Hicks, who was working for the Washington State Highway Department. That connection resulted in Jack Cram’s hiring in 1933 as the first state pilot for Washington, along with Byron Cooper, a lieutenant in the U.S. Army Reserve. Even as he was flying for the Washington State Highway Department, Cram was adding flying time to his logbook as a Marine Reserve pilot. In July 1934, then-Second Lt. Jack R. Cram was one of the six pilots that flew a formation of six Curtiss SBC Helldivers from Seattle to Montana. They were assigned to Observation Squadron 8 (VMO-8), probably based at NAS Sand Point. The purpose of the flight was to fulfill training requirements, though a public affairs component was part of the mission. The aircraft made demonstration and photo flights in Butte and Helena, Montana.1 The training for these aircraft fulfilled the early stages of the skills that Jack Cram demonstrated in WWII and the Korean War. Another connection to his wartime career was Capt. Lofton Henderson, who was promoted to captain while assigned to Observation Squadron 8. Henderson was killed in the early days of the 1942 . . . |

|

|

Howard Hugh’s Impromtu Beginning as a Helicopter Manufacturer

As 1949 approached, Howard Hughes was getting frustrated. His flying boat, the HK-1 Hercules, known to the world as the Spruce Goose, had made its one and only flight on November 2, 1947. Having come under intense Congressional scrutiny, it never made it into production. Likewise, his XF-11 photoreconnaissance airplane, originally set for a production run of 100 ships, was cancelled at war’s end. Even the XF-11’s maiden flight went awry when Hughes, who insisted on making the flight himself, was forced down in a fiery crash caused by a propeller malfunction. Miraculously he survived. It could be said that the late 1940s were not the best of years for the famous industrialist. Most annoying was that there were no new aircraft development projects under way at his plant in Culver City, California. Hughes hounded Rea Hopper, the general manager of his aeronautical operation at Hughes Aircraft Co., to keep busy sniffing out any aircraft development that showed promise.

In 1948, desperately seeking work for the company, Hughes took things in his own hands and flew his B-23, converted into an executive aircraft, to Wright Field in Ohio. He talked with Lt. Gen. Bill Craigie about latching up some kind of aircraft development contract. “Craigie told me he put Hughes in the helicopter business,” said Jack Real, who later became a close friend and confidant of the industrialist. “In the late forties, Howard asked for some

aircraft work as the HK-1 was through flying and the second XF-11 had completed its flight test program, and there was a recession in the aerospace industry. Craigie told him he did not have an airplane program but he had something as big as an airplane - the XH-17,” Real said.[1] This wasn’t exactly what Hughes had in mind (an airplane project), but rather the task of completing the fabrication and testing of a huge helicopter. Seeing little else on the horizon at. . . |

|

|

In 1923 Curtiss reorganized under the title Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Co. Inc. of Garden City, Long Is land, N.Y., and enjoyed one of its most successful years. Its products won the Pulitzer and Schneider Trophies and set the world’s speed record. Furthermore, the practicality of the wing radiator and Reed metal propeller were demonstrated in 1923. Fairey in England was buying rights to manufacture the highly successful D-12 engine that they would call the Felix, and production of the PW-8 pursuit was being set up to make it the standard Army pursuit plane. Finally, there was the one 1923 Curtiss product that stood out from all the others, the R2C Navy racer. Its influence on racing and pursuit plane design would be widespread and would long outlive it even though the 1923 Pulitzer was the only race in which an R2C would compete. After the Army’s stunning success in 1922 with the Curtiss R-6 racers, the Navy determined to make a comeback by investing in the development of updated racers, and two R2Cs were built with this requirement in mind. Their construction at Garden City was followed closely by Lt. Harold J. Brow, already chosen by the Navy as one of its racing pilots. The R2C was a direct descendant of the R-6 from which it differed in only minor details. Its design can be largely attributed to William L. Gilmore, Curtiss’ chief engineer, who was involved in the creation of all Curtiss racing airplanes from the“Texas Wildcat” to the R3C (before leaving aviation to make a comfortable fortune from zip fasteners). Arthur Nutt was largely responsible for the new D-12A engine. At this time the Navy was spending large sums of money to develop two new types of service engines — a bomber/torpedo plane engine of 700 hp and a fighter engine of 500 hp envisioned as an improved D-12. The Navy’s 1923 racers were to be flying test-beds for these new engines, and orders for 100 of each variety were to be placed. For the fighter’s engine, Curtiss redesigned the standard 465 hp D-12 with a 1/8” greater bore, and it produced 507 hp at 2,300 rpm in a dynamometer run. The increased power was also due in part to its high compression ratio of 5.8, but this necessitated a benzole-gasoline . . . |

|

|

[Editor’s Note: Many are aware that Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell was court-martialed in 1925 for his outspoken position regarding air power. Many are also aware that he accurately predicted the war with Japan, the attack of the Hawaiian Islands and the importance that air power would play in future conflicts. At the time many of these ideas were scoffed at by senior commanders. Few of us have had the opportunity to see firsthand what General Mitchell was actually espousing. The following article is the second in a series General Mitchell wrote for Aeronautics magazine in 1929, others of which will be presented in future issues.] Every airplane built is an asset for national defense. Each and every one, no matter whether it is called military or commercial, can be used in wartime, either for actual combat or transportation of goods and material, or for the training of pilots. Every air mechanic employed on commercial airways is efficient in case of war. Every airway, every landing field, all the aids to aerial navigation and the weather service, are assets. The tremendous military value of air power has burst on the world so suddenly that its realization is difficult for the average citizen. The idea is deeply ingrained into most of us that armies and navies must always conduct our wars, because they have done so from time immemorial. Such, however, is by no means the case today. The army has lost its mobility and with it the power of effecting a quick decision. To bring a war to a successful conclusion, the vital points of the enemy must be seized or controlled, so as to prevent him from living in his accustomed way and carrying on his usual functions of government. Armies were opposed by other armies in the accomplishment of this task. In other words, walls of men were put up in front of the great cities and vital centers to protect them. In the days when populations were not as great per square mile as now, and it was difficult to support armies, the small forces employed were capable of considerable movement, but as time went on the armies grew larger and larger, became more immobile and unwieldy, and incapable of striking or acting quickly. The distance from Washington to Richmond, Va., is 121 miles. In the Civil War, it took the Union Army about five years to get there. An airplane would have covered the distance in less than one hour. In the European war, the armies faced each other along a 250 mile front. They went backward and forward for about 60 miles until the end of the contest. Men were killed by the thousands by machine gun fire, they were shot up with cannon, stuck with bayonets and devoured by disease. This modern and “humane” warfare could only result in one thing, the utter destruction of all the participants in such a combat. It ceased to be war and was merely a slaughterhouse performance in which no science, art or ingenuity was involved. The European war, except for a few battles at the beginning, was one of the most uninteresting that history gives us. Armies have now reached a stalemate and the old theory of war, that victory meant the destruction of the hostile main army, is untenable. The idea behind this was that once the army was destroyed, all the vital centers of the opposing country lay open to the invader. Now, however, armies have become mere holders of ground and air power is the only thing that can go quickly and surely to the vital centers of the enemy. If you tie aviation to an army you are going to stop its effectiveness at once. Suppose, for instance, that Chicago and New York were the capitals and vital centers of two opposing states. They are about 800 miles apart. Suppose that the military force of Chicago consisted of a great army of one million men with only aviation enough to act as a means of reconnaissance and observation for its infantry and artillery. Suppose that the army of New York consisted of 100,000 men but that they had an air force of 1,000 airplanes capable of flying to Chicago and back, and each capable of carrying two tons of projectiles, air torpedoes, bombs, gas projecting apparatus and guns. Suppose this force were launched at Chicago, with 2,000 tons of projectiles. They would make the trip in seven hours. They could not only force the evacuation of the city and set on fire all the towns and manufacturing plants around . . . |

|

|

Recently, while getting rid of items from the storage area in my garage, I came across a sealed cardboard box that had not been opened for over five decades. After opening this mini time capsule, it was discovered that among other things, the box contained the flight navigational logs for a cross-country flown over 50 years ago. While reviewing the material pertaining to this almost forgotten event, I began to recall the following: In 1955, I was an instructor pilot assigned to the 3530th Pilot Training Squadron, Bryan AFB, Texas. Like most young pilots, I took advantage of every opportunity to increase my total flight hours. Actually, during my Training Command tour, there were few weekends when I did not fly student training flights. Once, while engaged in this type of training, a student and I had flown three flights in one day. Two of the flights had been at or above 40,000 ft. attitude. Unfortunately, after the third flight, the student exhibited symptoms of hypoxia. The T-33 cockpit pressurization system was never anything to brag about. Regardless, from that time on, when conducting student cross-country training, while assigned to Bryan, I was restricted to two flights a day and only one could be at, or above, 40,000 feet. At the time, this situation seriously jeopardized my plan to fly over all 48 states within the United States, and the District of Columbia, during one cross-country. Remember, this was before Alaska or Hawaii was a state. Providence stepped in, however, when I was asked to give a so-called “behind-the-line” pilot a 1,000 mile cross-country checkout. Briefly, a behind-the-line pilot is a fully rated individual assigned duty other than on the flight line. I quickly agreed, since this would not involve a student pilot, negating the previously stated restrictions. This opportunity materialized in November, not the best time of the year for the type of flight I had in mind. Unfortunately, I can no longer remember the name of the major that shared this experience with me. I do recall, however, how surprised he was to learn what his crosscountry check out was going to consist of. In an effort to reduce our ground time, I had prepared all the . . . |

|

|

Few Air Force officers – if any – have been so controversial and then so forgotten. It’s not fair – at least not the“forgotten” part. In the short span of four-and-a-half years, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s second son enjoyed a truly meteoric rise in the Army Air Forces, beginning with his appointment as a Captain in the Specialist Reserve on his 30th birthday in September 1940. When his father died in April 1945, Elliott’s extraordinary career was effectively over. After the president’s funeral, Elliott did not return to his command in Europe, and he mustered out on VJ-Day, August 15, 1945. Elliott Roosevelt’s achievements in the Air Corps were legendary – some of them literally so. Yet his real contributions, particularly in reconnaissance, were valuable and enduring. It’s just that for every heroic feat, there was at least another scandal, another controversy, another crisis that sometimes even lurched dangerously towards criminality. Congress investigated Elliott’s wide-ranging activities eight times, from 1934 to 1973. He skated every time.[1] During his father’s administration, Elliott’s escapades were front-page news and regular fodder for the gossip columnists. Why his zigzag career has been largely forgotten today, I do not know, but I found during my research of his biography enough hair-raising material to find the oblivion outrageously unjust. Perhaps his strange life was considered unsuitable for historical investigation, especially by those who carefully police the memory of Franklin D. Roosevelt and his family. Perhaps too many murky episodes of that time would be resurrected for the popular taste. Or perhaps it is just a glitch in historiography. The importance of Elliott Roosevelt’s work, especially in aeronautics, cannot be gainsaid. Mostly by virtue of his pedigree and name, Elliott managed to intersect and often affect some of the most important developments in aviation, in the air war against Germany, and in great power diplomacy. In this venue I shall leave out the non-aviation activities, although they were as colorful and reckless as one can conceive. There is more than enough in his flying career to fill a highly entertaining book. Before the War Mother Eleanor said he “couldn’t see 10 feet without his glasses,” which he seldom wore. In truth, he registered 20/200 in one eye and 20/300 in the other. This would raise some eyebrows when finally he was rated a command pilot in . . . |

|

|

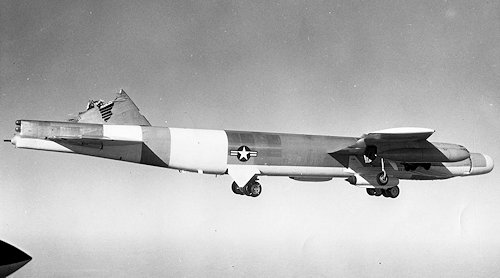

A Very Short Tale, The Boeing B-52 Stratofortress

Aviation enthusiasts are offered the following question: what airplane was conceived in the late 1940s, now celebrates 63 years in-service, is a ”Nam” Vet, survived the Cold War, required the expertise and products of 2,819 subcontractors and vendors, massive amounts of aircraft grade sheet metal, exited the factory with numerous wrinkles, thus looking old from the get-go, suffered death by Sidewinder, generated large radar returns, tumbled from the sky from Soviet V-750 missile hits, released a thermo-nuclear weapon on the Greenland ice cap, stabbed a KC-135 tanker in the face with a GAM-77 Hound Dog, was hammered into junk by hail, been ripped into by clear air turbulence (CAT), endured continuous updates, became a mothership to various missiles, decoys, experimental aircraft and rocket-ramjet vehicles, and finally, with crew trussed up in pressure suits, reached 59,000 feet and still flies today? The correct guess is the Boeing B-52, but as the Brits say,“spot on ole chap,” but sorry, no Havana cigar. While the Boeing Model 450 or B-47 Stratojet was still being wrung out and “oil-canning” its way into USAF service with the Strategic Air Command (SAC), Boeing engineers were busy preparing designs for their Model 474 long-range heavy bomber powered by six Wright T-35 turboprop engines. Drawings and models were constructed by in-house wind tunnel master model builders - they called it a nightmare because it resembled a Russian style bomber. One Boeing retiree stated with slightly curled lips that the engineers either suffered food indigestion and consequent nightmares immediately prior to creating their Model 474 turboprop or XB-55, or were English speaking Soviet engineers on a secret “exchange” program. The strongest printable words told to the author were, “it was damned ugly,” meaning few in the model shops liked it - neither did the Air Force for that matter. The USAF rejected this proposal and counter-proposed an all-turbojet bomber. A Boeing team visiting Wright-

Patterson AFB drew up a rough specs draft including a balsawood model during the visit in a Dayton, Ohio, hotel room - the result was Boeing won a new bomber contract. During late November 1951, prototype Model 464-67 XB-52 serial number 16428 (tail number 49-230) was rolled,. . . |

|

|

Forum of Flight

The FORUM is presented as an opportunity for each member to participate in the Journal by submitting interesting or unusual photographs. Negatives, blackand-white or color photos with good contrast may be used if they have smooth surfaces. Send submissions to the Editorial Committee marked “Forum of Flight,” P.O. Box 3023, Huntington Beach, CA 92605-3023. Mark any material to be returned: “Return to (your name and complete address).” Please include as much information as possible about the photo such as: date, place, names, etc., plus proper credit (it may be part of your collection but taken by another photographer) |

|

|

For the aviation enthusiast who was young of age, or young at heart, during the Golden Age of Aviation, it is not an exaggeration to say, decades later, that they were fortunate witnesses to a “Camelot (idyllic) period of aviation.” This romance with aviation, influenced by the colorful and unique aircraft and magnificent dirigibles of the period, was reinforced by many exciting Hollywood movies, aviation magazines, and photos of colorful aircraft. These visuals were complemented by action-oriented air shows, flying exhibitions, and air races.

|

|

|

News and Comments is a special section that allows the Society to publish corrections, addendums, comments and short essays contributed by Society members. Members are encouraged to submit these to the Editorial Committee marked “News & Comments,” P.O. Box 3023, Huntington Beach, CA 92605-3023. Mark any material to be returned: “Return to (your name and complete address).” |

|

|

Additions, corrections and general comments from AAHS members and other individuals that have contact the Society. |

|

American Aviation Historical Society

American Aviation Historical Society